Sometime this month, Reddit will go public at a valuation of $6.5bn. Select Redditors were offered the chance to buy stock at the initial listing price, which it hasn’t announced yet but is expected to be in the range of $31-34 per share. Regardless of the actual price, I wouldn’t be surprised if Reddit shares quickly fall below the IPO price, based on the fact that Reddit is an absolute dog of a company, losing $90.8 million on $804 million of revenue in 2023 and never having turned a profit. Reddit's S1 (the initial registration form for taking a company public) laughably claims that advertising on the site is "rapidly evolving" and that it is "still in the early phases of growing this business," with "this business" referring to one that Reddit launched 15 years ago.

The Reddit IPO is one of the biggest swindles in corporate history, where millions of unpaid contributors made billions of posts so that CEO Steve Huffman could make $193 million in 2023 while laying off 90 people and effectively pushing third party apps off of the platform by charging exorbitant rates for API access, which in turn prompted several prolonged “strikes” by users, with some of the most popular subreddits going silent for a short period of time. Reddit, in turn, effectively “couped” these subreddits, replacing their longstanding moderators with ones of its own choosing — people who would happily toe the party line and reopen them to the public.

None of the people that spent hours of their lives lovingly contributing to Subreddits, or performing the vital-but-thankless role of moderation, will make a profit off of Reddit's public listing, but Sam Altman will make hundreds of millions of dollars for his $50 million investment from 2014. Reddit also announced that it had cut a $60 million deal to allow Google to train its models on Reddit's posts, once again offering users nothing in return for their hard work.

Huffman's letter to investors waxes poetic about Redditors' "deep sense of ownership over the communities they create," and justifies taking the company public by claiming that he wants "this sense of ownership to be reflected in real ownership" as he offers them a chance to buy non-voting stock in a company that they helped enrich. Huffman ends his letter by saying that Reddit is "one of the internet's largest corpuses of authentic and constantly updated human-generated experience" before referring to it as the company's "data advantage and intellectual property," describing Redditors' posts as "data [that] constantly grows and regenerates as users converse."

We're at the end of a vast, multi-faceted con of internet users, where ultra-rich technologists tricked their customers into building their companies for free. And while the trade once seemed fair, it's become apparent that these executives see users not as willing participants in some sort of fair exchange, but as veins of data to be exploitatively mined as many times as possible, given nothing in return other than access to a platform that may or may not work properly.

This is, of course, the crux of Cory Doctorow's Enshittification theory, where Reddit has moved from pleasing users to pleasing its business customers to, now, pleasing shareholders at what will inevitably be the cost of the platform's quality.

Yet what's happening to the web is far more sinister than simple greed, but the destruction of the user-generated internet, where executives think they've found a way to replace human beings making cool things with generative monstrosities trained on datasets controlled and monetized by trillion-dollar firms.

Their ideal situation isn't one where you visit distinct websites with content created by human beings, but a return to the dark ages of the internet where most traffic ran through a series of heavily-curated portals operated by a few select companies, with results generated based on datasets that are increasingly poisoned by generative content built to fill space rather than be consumed by a customer.

The algorithms are easily-tricked, and the tools used to trick them are becoming easier to use and scale.

And it's slowly killing the internet.

Degenerative AI

After the world's governments began their above-ground nuclear weapons tests in the mid-1940s, radioactive particles made their way into the atmosphere, permanently tainting all modern steel production, making it challenging (or impossible) to build certain machines (such as those that measure radioactivity). As a result, we've a limited supply of something called "low-background steel," pre-war metal that oftentimes has to be harvested from ships sunk before the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, including those dating back to the Roman Empire.

Generative AI models are trained by using massive amounts of text scraped from the internet, meaning that the consumer adoption of generative AI has brought a degree of radioactivity to its own dataset. As more internet content is created, either partially or entirely through generative AI, the models themselves will find themselves increasingly inbred, training themselves on content written by their own models which are, on some level, permanently locked in 2023, before the advent of a tool that is specifically intended to replace content created by human beings.

This is a phenomenon that Jathan Sadowski calls "Habsburg AI," where "a system that is so heavily trained on the outputs of other generative AIs that it becomes an inbred mutant, likely with exaggerated, grotesque features." In reality, a Habsburg AI will be one that is increasingly more generic and empty, normalized into a slop of anodyne business-speak as its models are trained on increasingly-identical content.

LinkedIn, already a repository of empty-headed corpo-nonsense, already lets users write generate messages, profiles and job descriptions using AI, and anything you create using these generative features is immediately fed back into Azure's OpenAI models owned by its parent company Microsoft, which invested $10 billion in OpenAI in early 2023. While LinkedIn is yet to introduce fully-automated replies, Chrome extensions already exist to flood the platform with generic responses, feeding more genericisms into the mouth of Microsoft and OpenAI's models.

Generative AI also naturally aligns with the toxic incentives created by the largest platforms. Google's algorithmic catering to the Search Engine Optimization industry naturally benefits those who can spin up large amounts of "relevant" content rather than content created by humans. While Google has claimed that their upcoming "core" update will help promote "content for people and not to rank in search engines," it’s made this promise before, and I severely doubt anything meaningfully changes. After all, Google makes up more than 85% of all search traffic and pays Apple billions a year to make Google search the default on Apple devices.

And because these platforms were built to reward scale and volume far more often than quality, AI naturally rewards those who can find the spammiest ways to manipulate the algorithm. 404 Media reports that spammers are making thousands of dollars from TikTok's creator program by making "faceless reels" where AI-generated voices talk over spliced-together videos ripped from YouTube, and a cottage industry of automation gurus are cashing in by helping others flood Facebook, TikTok and Instagram with low-effort videos that are irresistible to algorithms.

Amazon's Kindle eBook platform has been flooded with AI-generated content that briefly dominated bestseller lists, forcing Amazon to limit authors to publishing three books a day. This hasn't stopped spammers from publishing awkward rewrites and summaries of other people's books, and because Amazon's policies don't outright ban AI-generated content, ChatGPT has become an inoperable cancer on the body of the publishing industry.

"Handmade" goods store Etsy has its own AI problem, with The Atlantic reporting last year that the platform was now pumped full of AI-generated art, t-shirts and mugs that, in turn, use ChatGPT to optimize listings to rank highly in Google search. As a profitable public company, Etsy has little incentive to change things, even if the artisanal products on the platform are being crowded out by generative art pasted on drop-shipped shirts. eBay, on the other hand, is leaning into the spam, offering tools to generate entire listings based on a single image using generative AI.

The Wall Street Journal reported last year that magazines are now inundated with AI-generated pitches for articles, and renowned sci-fi publisher Clarkesworld was forced to close submissions after receiving an overwhelming amount of AI-generated stories. Help A Reporter Out used to be a way for journalists to find potential sources and quotes, except requests are now met with a deluge of AI-generated spam.

These stories are, of course, all manifestations of a singular problem: that generative artificial intelligence is poison for an internet dependent on algorithms.

There are simply too many users, too many websites and too many content providers to manually organize and curate the contents of the internet, making algorithms necessary for platforms to provide a service. Generative AI is a perfect tool for soullessly churning out content to match a particular set of instructions — such as those that an algorithm follows — and while an algorithm can theoretically be tuned to evaluate content as "human," so can scaled content be tweaked to make it seem more human.

Things get worse when you realize that the sheer volume of internet content makes algorithmic recommendations a necessity to sift through an ever-growing pile of crap. Generative AI allows creators to weaponize the algorithms' weaknesses to monetize and popularize low-effort crap, and ultimately, what is a platform to do? Ban anything that uses AI-generated content? Adjust the algorithm to penalize videos without people's faces? How does a platform judge the difference between a popular video and a video that the platform made popular? And if these videos are made by humans and enjoyed by humans, why should it stop them?

Google might pretend it cares about the quality of search results, but nothing about search's decade-long decline has suggested it’s actually going to do anything. Google's spam policies have claimed for years that scraped content (outright ripping the contents of another website) was grounds for removal from Google, but even the most cursory glance at any news search shows how often sites thinly rewrite or outright steal others' content. And I can't express enough how bad (yet inevitable) the existence of the $40 billion Search Engine Optimization industry is, and how much of a boon being able to semi-automate the creation and optimization of content to the standards of an algorithm that Google has explained in exhaustive detail. While it's plausible that Google might genuinely try and fight the influx of SEO-generated articles, one has to wonder why it’d bother to try now after spending decades catering to the industry.

As we speak, the battle that platforms are fighting is against generative spam, a cartoonish and obvious threat of outright nonsense, meaningless chum that can and should (and likely will) be stopped. In the process, they're failing to see that this isn't a war against spam, but a war against crap, and the overall normalization and intellectual numbing that comes when content is created to please algorithms and provide a minimum viable product for consumers. Google's "useless" results problem isn't one borne of content that has no meaning, but of content that only sort of helps, that is the "right" result but doesn't actually provide any real thought behind it, like the endless "how to fix error code X" results full of well-meaning and plausibly helpful content that doesn't really help at all.

The same goes for Etsy and Amazon. While Etsy's "spam" is an existential threat to actual artisans building something with their hands, it's not actual spam — it's cheaply-made crap that nevertheless fulfills a need and sort of fits Etsy's remit. Amazon doesn't have any incentive to get rid of low-quality books that sell for the same reason that it doesn't get rid of its other low-quality items. People aren't looking for the best, they're looking to fulfill a need, even if that need is fulfilled with poorly-constructed crap.

Platforms likely conflate positioning with popularity, failing to see the self-fulfilling prophecy of an algorithm making stuff popular because said stuff is built to please the algorithm creating more demand for content to please the algorithm. "Viral" content is no longer a result of lots of people deciding that they find something interesting — it's a condition created by algorithms manipulated by forces that are getting stronger and more nuanced thanks to generative AI.

We're watching the joint hyper-scaling and hyper-normalization of the internet, where all popular content begins to look the same to appeal to algorithms run by companies obsessed with growth. Quality control in AI models only exists to stop people from nakedly exploiting the network through unquestionably iniquitous intent, rather than people making shitty stuff that kind of sucks but gets popular because an algorithm says so.

This isn't a situation where these automated tools are giving life to new forms of art or interesting new concepts, but regurgitations of an increasingly less unique internet, because these models are trained on data drawn from the internet. Like a plant turning to capture sunlight, parts of the internet have already twisted toward the satisfaction of algorithms, and as others become dependent on generative AI (like Quora, which now promotes ChatGPT-generated answers at the top of results), so will the web become more dependent and dictated by automated systems.

The ultimate problem is that this morass of uselessness will lead companies like Google to force their generative AIs to "fix" the problem by generating answers to sift through the crap. Amazon now summarizes reviews using generative AI, legitimizing the thousands of faked and paid-for reviews on the platform and presenting them as verified and trusted information from Amazon itself. Google has already been experimenting with its "Search Generative Experience" that summarizes entire articles on iOS and Chrome, and Microsoft's Bing search has already integrated summaries from Copilot, with both basing their answers off of a combination of search and training data.

Yet in doing so, these platforms gain a dangerous hold on the world's information. Google's deal with Reddit also gave it real time access to Reddit's content, allowing it to show Reddit posts natively in search (and directly access Reddit posts data for training purposes). Yet at some point these portals will generate an answer based off of the data they have (or have access to, in the case of Tumblr and Wordpress) rather than linking you to a place where you can find an answer by reading something created by another person. There could be a future where the majority of web users experience the web through a series of portals, like Arc Search's "browse for me" feature, which visits websites for you and summarizes their information using AI.

Right now, the internet is controlled by a few distinct platforms, each one intent on interrupting the exploratory and creative forces that made the web great. I believe that their goal is to intrude on our ability to browse the internet, to further obfuscate the source of information while paying the platforms for content that their users make for free. Their eventual goal, in my mind, is to remove as much interaction with the larger internet as possible, summarizing and regurgitating as much as they can so that they can control and monetize the results as much as possible.

On some level, I fear that the current platforms intend to use AI to become something akin to an Internet Service Provider, offering "clean" access to a web that has become too messy and unreliable as a direct result of the platforms' actions, eventually finding ways to monetize your information's prominence in their portals, models and chatbots. As that happens, it will begin to rot out the rest of the internet, depriving media entities and social networks of traffic as executives like Steve Huffman cut further deals to monetize free labor with platforms that will do everything they can to centralize all internet traffic to two or three websites.

And as the internet becomes dominated by these centralized platforms and the sites they trawl for content, so begins the vicious cycle of the Habsburg AI. OpenAI's ChatGPT and Anthropic's Claude are dependent on a constant flow of training data to improve their models, to the point that it's effectively impossible for them to operate without violating copyright. As a result, they can't be too picky when it comes to the information they choose, meaning that they're more than likely going to depend on openly-available content from the internet, which as I've suggested earlier will become increasingly normalized by the demands of algorithms and the ease of automating the generic content that satisfies them.

I am not saying that user-generated content will disappear, but that human beings cannot create content at the scale that automation can, and when a large chunk of the internet is content for robots, that is the content that will inform tomorrow's models. The only thing that can truly make them better is more stuff, but when the majority of stuff being created isn't good, or interesting, or even written for a human being, ChatGPT or Claude's models will learn the rotten habits of rotten content. This is why so many models' responses sound so similar — they're heavily dependent on the stuff they're fed for their outputs, and so much of their "intelligence" comes from the same training data.

It's a different flavor of the same problem — these models don't really "know" anything. They're copying other people's homework.

As an aside, I also fear for the software code that's created by generative AI products like GitHub Co-pilot. A study by security firm Snyk found that GitHub Copilot and other AI-powered coding platforms, which were trained on publicly-available code (and based on the user's own codebase), can replicate existing security issues, proliferating problems rather than fixing them. NYU's Center for Cybersecurity also found in 2023 study that CoPilot generated code with security vulnerabilities 40% of the time.

These are also the hard limits that you're going to see with generative images and video. While the internet is a giant hole of content you can easily and cheaply consume for training, visual media requires a great deal of significantly more complex data — and that’s on top of the significant and obvious copyright issues. ChatGPT's DALL-E (images) and Sora (video) products are, as I've noted, limited by the availability of ways to teach them as well as the limits of generative AI itself, meaning that video may continue to dominate the internet as text-based content finds itself crowded out by AI-generated content. This may be why Sam Altman is trying to claim that giant AI models are not the future — because there may not be enough fuel to grow them much further. After all, Altman claims that any one data source "doesn't move the needle" for OpenAI.

There's also no way to escape the fact that these hungry robots require legal plagiarism, and any number of copyright assaults could massively slow their progress. It's incredibly difficult to make a model forget information, meaning that there may, at some point, be steps back in the development of models if datasets have to be reverted to previous versions with copyrighted materials removed.

The numerous lawsuits against OpenAI could break the back of the company, and while Altman and other AI fantasists may pretend that these models are an intractable path to the future of society, any force that controls (or makes them pay for) the data that they use will kneecap the company and force them to come up with a way to make these models ethically.

Yet the world I fear is one where these people are allowed to run rampant, turning unique content into food for an ugly, inbred monster of an internet, one that turns everybody's information sources into semi-personalized versions of the same content. These people have names — Sam Altman of OpenAI, Sundar Pichai of Google, Mark Zuckerberg of Meta (which has its own model called LLaMA), Dario Amodei of Anthropic, and Satya Nadella of Microsoft — and they are responsible for trying to standardize the internet and turn it into a series of toll roads that all lead to the same place.

And they will gladly misinform and disadvantage billions of people to do so. Their future is one that is less colorful, less exciting, one that caters to the entitled and suppresses the creative. Those who rely on generative AI to create are not creators any more than a person that commissions a portrait is an artist. Altman and his ilk believe they're the new Leonardo Da Vincis, but they're little more than petty kings and rent-seekers trying to steal the world's magic.

They can, however, be fought. Don't buy their lies. Generative AI might be steeped in the language of high fantasy, but it’s a tool, one that they will not admit is a terribly-flawed and unprofitable way to feed the growth-at-all-costs tech engine. Question everything they say. Don't accept that AI "might one day" be great. Demand that it is today, and reject anything less than perfection from men that make billions of dollars shipping you half-finished shit. Reject their marketing speak and empty fantasizing and interrogate the tools put in front of you, and be a thorn in their side when they try to tell you that mediocrity is the future.

You are not stupid. You are not "missing anything.” These tools are not magic — they're fantastical versions of autocomplete that can't help but make the same mistakes it's learned from the petabytes of information it's stolen from others.

And they will gladly misinform and disadvantage billions of people to do so. Their future is one that is less colorful, less exciting, one that caters to the entitled and suppresses the creative. Those who rely on generative AI to create are not creators any more than a person that commissions a portrait is an artist. Altman and his ilk believe they're the new Leonardo Da Vincis, but they're little more than petty kings and rent-seekers trying to steal the world's magic."

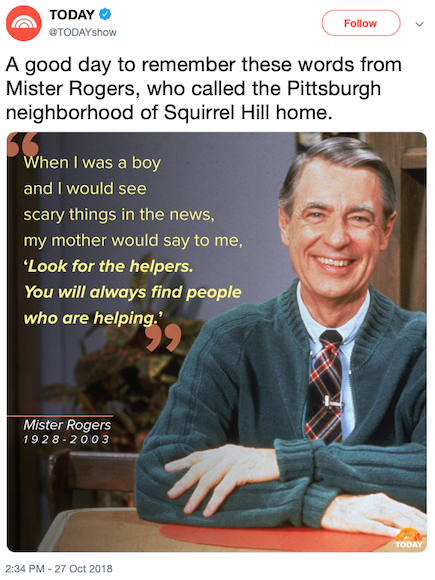

After the senseless calamity of a mass shooting, people seek comforts—even small ones—in the face of horror. One of those small comforts has come to be Fred Rogers’s famous advice to look for the helpers. “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news,” Rogers said to his television neighbors, “my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’”

Lately, whenever something goes horribly wrong, someone offers up Rogers’s phrase or a video in which he shares it as succor: during the Thai cave rescue, in response to the U.S. family-separation policy, after a school-bus accident in New Jersey, following a fatal explosion in Wisconsin, in the aftermath of a van attack in Toronto, in the wake of the Stoneman Douglas school massacre, and more.

And so it was no surprise when “Look for the helpers” reared its head again after a gunman killed 11 people and wounded six others in a Pittsburgh synagogue on Saturday. Not just because the shooting marked another tragedy in America, but also because Rogers, who died in 2003, was a longtime resident of the Squirrel Hill neighborhood, where the synagogue is located. It’s as if all the other crimes and accidents in which Fred Rogers has been invoked were rehearsing for this one. “A Massacre in the Heart of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood,” reads the headline of Bari Weiss’s New York Times column on the slaughter.

Once a television comfort for preschoolers, “Look for the helpers” has become a consolation meme for tragedy. That’s disturbing enough; it feels as though we are one step shy of a rack of drug-store mass-murder sympathy cards. Worse, Fred Rogers’s original message has been contorted and inflated into something it was never meant to be, for an audience it was never meant to serve, in a political era very different from where it began. Fred Rogers is a national treasure, but it’s time to stop offering this particular advice.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood aired from 1968 to 2001, and it continues to run in syndication and on streaming services today. It was intended for preschoolers, which means that anyone who had kids under age 5 and owned a television, and anyone who was a child of that age since then, probably became neighbors with Mr. Rogers. That covers just about the entire U.S. population, which explains why the man and his show are so recognizable. The program’s ubiquity also speaks to the applicability of the “Look for the helpers” idea—it’s easy to quote or cite on-air or online, and it binds people of many generations and walks of life in tender recognition.

But it was never meant to do that much work. Rogers was an expert at translating the complex adult world in terms kids could understand: a grown-up emissary to a children’s nation. “Look for the helpers” was advice for preschoolers. But somehow, when it got transformed into a meme, the sentiment was adopted by adults as if they were 3-year-olds.

It’s a powerful notion for kids, especially very young ones. Fred Rogers Productions maintains a resource for parents on talking to children about tragic events that explains why. Children are small and fragile. They rely on adults for almost everything, from daily care to emergency rescue. “Look for the helpers” is a tactic that diverts a child’s distress toward safety.

Even for preschoolers, it was never meant to be used alone. On the part of the Fred Rogers website about tragic events, “focusing on the helpers” appears among an eight-bullet list of tips. It also advises parents to turn off the television, maintain regular routines, and offer physical affection. Not only was this advice meant for children; it was intended as part of a holistic approach to managing a small child’s worry during a crisis.

Read: The quietly radical [Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood]

Seen in this context, to extract and deploy “Look for the helpers” as sufficient relief for adults is perverse, if telling. Grown-ups sometimes feel as helpless as children, and on the internet, where this meme mostly proliferates, distressed social-media posts, futile emoji, and forlorn crowdfunding campaigns have taken the place of social and political action. Which isn’t to say that that sort of action is easy to carry out anymore. For a populace grappling with voter suppression, wealth inequality, and the threat of a police state, among other perils, it’s not always clear how citizens can effect change in their communities and their nation. Ironically, when adults cite “Look for the helpers,” they are saying something tragic, not hopeful: Grown-ups now feel so disenfranchised that they implicitly self-identify as young children.

Among critics of “Look for the helpers” as a meme, a common objection is that just looking for the helpers is insufficient, at least for adults. Instead, you’re supposed to strive to “be a helper,” a variation on the original that’s almost become its own meme.

But that assumes anyone knows who counts as a “helper” anymore.

Rogers attributed the line to his mother, who probably gave him the advice during the 1930s. Things were difficult then, but tragedy came in a different form. Illness and death, natural disaster, economic despair, and, soon enough, global war. In all these cases, there remains some clear line between a threat and its relief.

Those matters would complicate themselves in the 1960s and beyond, when Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood entered its heyday. The show addressed current events, in its own way, from violence to segregation to war. But even in the 1980s, when the Cold War still raged, threats like tornadoes still preoccupied “Look for the helpers” wisdom.

Fred Rogers diligently refined the language he used on his show, transforming simple but ambiguous ideas into polished, sophisticated ones that take children’s lives into account. It is dangerous to play in the street would become Your favorite grown-ups can tell you where it is safe to play. It is important to try to listen to them, and listening is an important part of growing. In that example, your favorite grown-ups accounts for all sorts of circumstances, from guardians who are not parents to authorities the child trusts for established reasons. It’s a genius phrase, and classic Fred Rogers fare.

“Helpers” is a similar one. It covers official authorities like police and firefighters, but also laypeople like bystanders and Good Samaritans.

Even so, it seems that Rogers meant the term to refer mostly to trained service professionals in a position of authority. In a 1986 newspaper column about the helpers concept, Rogers was still leaning on natural disasters as the paradigm for terror, and on childhood memories of newspapers, radios, and newsreels that fomented fear. In a 1999 interview with the Television Academy Foundation, Rogers clarified the idea more, talking about the people “just on the sidelines” of a tragedy. His hope was that media might show actors like “rescue teams, medical people, anybody who is coming in to a place where there’s a tragedy.”

This wisdom should have felt a little romantic in its aspirations, even in the 1980s and ’90s. Who “helps” avert global nuclear catastrophe, or climate change, for example? But today, the idea of helpers on the sidelines of horrific disasters isn’t just quaint. It’s dangerous.

After the Pittsburgh attack, President Donald Trump told reporters that the Tree of Life synagogue should have “had protection in mind,” by which he probably meant armed guards, or “good guys with guns.” Never mind the fact that the shooter had wounded four police officers during the standoff, thanks in part to the semiautomatic rifle with which he was reportedly armed. Those who advocate for guns everywhere see gunmen as the “helpers.” Those who do not construe the people who would limit access to them, or who would curtail domestic terrorism and white supremacy, as the “helpers” instead. The conflict over who gets to count as a helper is a complex amalgam of political and social conditions. But unfortunately, adapting Fred Rogers’s concept for the universe of kids to the world of adults allows any speaker’s favorite notion of “help” to fill in the blank.

The suspect himself, a man named Robert Bowers, appears to have construed his own actions as heroic rather than villainous. Bowers reportedly shouted “All Jews must die” before opening fire at Tree of Life. He advanced conspiracy theories about a Jewish incursion of government and society, including the false idea that the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, a humanitarian nonprofit, was funded by George Soros to import immigrants for violence. On Fox News, Lou Dobbs gave prominent airtime to an advocate of this view the same day as the synagogue massacre. And Trump has spread similar fears about criminal incursions by immigrants, not to mention other angry falsehoods. Bowers, Trump, Dobbs, and others all consider themselves “the helpers.” For those who want to look for them—or to be them—in a time of crisis, ideas of help and harmful actions are dangerously conflated.

Fred Rogers has a saintlike legacy for good reason. He touched people of all backgrounds and faiths. He modeled goodness and character. But his was never a gospel for grown-ups. It was designed for children, and entrusted to adults to carry out with kids’ interests in mind. (His attempt at a show for adults failed.)

We must stop fetishizing Rogers’s advice to “look for the helpers” as if it had ever been meant for us, the people in charge—even in moments when so many of us feel powerless. As an adult, it feels good to remember how Mr. Rogers made you feel good as a child. But celebrating that feeling as adults takes away the wrong lesson. A selfish one. We were entrusted with these insights to make children’s lives better, not to comfort ourselves for having failed to fashion the adult world in which they must live.

Last year, Alex, a 19-year-old in California who runs a network of Instagram pages dedicated to publishing memes, became so frustrated with the current apps for making memes that she hired a developer to build her own. She spent $3,000 on the project, which she says has saved her hours of time and frustration.

“I don’t want to say it’s a competitive edge, because at the end of the day that’s not really what determines if a meme does well,” says Alex, whose pages have 5 million collective followers. “But for people who care enough about having memes perfect it makes a difference.” (Like all members in this story, Alex runs her pages anonymously, and asked to be referred to by her first name only to protect her privacy.)

As memes have increasingly dominated social platforms like Instagram, the methods for making them remain largely rudimentary. Many large accounts on Instagram treat Twitter as a content-management system for laying out images with text, but that comes with huge limitations. As memes become increasingly visually complex, they’re forcing meme makers—from professionals who run massive pages, to amateurs, to those just starting out—to rely on a patchwork of unreliable photo-editing tools.

“I use four apps to make a meme,” says Andy, who runs the Instagram meme page @heckoffsupreme. “There’s not one app I can go to for everything I need, not even close.”

“It’s ad hoc,” says Terry, who runs the page @socialpracticemafia and has used a slew of photo- and video-editing apps to make memes. “You know the term bricolage? It’s basically making due. It’s like that.”

Years ago, when classic macro-memes with Impact font—like Success Kid, Condescending Wonka, and Business Cat—became popular, there were tons of easy online meme generators. Unfortunately, as memes have evolved, the majority of top meme-making apps in Apple’s App Store have failed to adopt to more modern formats, rendering them semi-useless.

“You’d only use one of those now to be ironic about how terrible they are,” says Terry. “It’s funny that there’s been this regression to something that’s actually less efficient, because the style of memes has changed. I don’t think anyone is designing these apps to make the kind of weird post-dank memes that are being made now.”

The most popular format for large meme pages is still one that looks like a tweet with an image attached: a photo or video on the bottom, Arial-font text on top, and a white background. But over the past several months, there’s been a sea-change in the meme community, according to several top memers. Meme accounts that post more complex, artistic memes—including object-labeling memes, creative photo-editing memes, or memes with lots of text—have begun to gain popularity and online clout, and thousands of amateur meme accounts have sprung up, copying their style.

“The biggest difference is there’s way more information packed into most memes today than Impact-font memes,” says Cindie, who runs the meme account @males_are_cancelled. “The average person has viewed so much of this content, their ability to understand the nuance within newer meme format has increased.”

“I’m 20, maybe because it’s a new thing, but I think younger people are into more absurd, surreal humor,” says Chris, who creates highly visual memes under the handle @young__nobody. “Those big meme pages would make fun of us or call us weird niche members with the kooky fonts, but the whole scene has grown a lot in the past year,” says Loren, also known as @Whiskey.rat.

But to create in this new genre of memes means to rely heavily on apps that were not built with meme creators in mind. Phonto, one of the most popular apps for making object-labeling memes, has a steep learning curve and is plagued with bugs. “Losing my work has happened to me constantly,” says Andy, who has also relied on an app called InShot. “Sometimes things will shut down and be gone and I’ll have to start over. It becomes really time-consuming.” PicsArt, another photo-editing tool, is a mainstay for many memers who use it to watermark their work, but is notorious for its distracting pop-up ads.

For video memes, many people rely on PicPlayPost, but the app was not built for making memes and doesn’t include some more advanced features that many memers crave. “We didn’t create PicPlayPost with the intention of going after the meme community, but given the tools we have it doesn’t surprise me that it’s building momentum in that group,” says Daniel Vinh, who heads marketing for Mixcord, the parent company of PicPlayPost. “If any of these memers want to reach out and talk to us about the top five features they want or need, we’d be more than happy to have a brainstorm session on how we can make that happen.”

In the meantime, some memers have found the current suite of mobile applications so lacking that they choose to create their memes on desktop computers instead. “On your phone, you’re never going to be able to do as much as you could as on a computer,” says Noam, who memes under the account @listenintospitandgettingparamoredon.

Ronnie, who memes under the handle @mspainttrash, is part of a group of meme makers that works exclusively in MS Paint. “It’s so readily available. You don’t have to download it. It’s on any PC. It’s the most straightforward paint app that you could possibly use,” he says. “I’ve made maybe two memes total on my phone.”

Recognizing this need, some apps have emerged in recent months to corner the market. But building the killer meme app is incredibly challenging. Many memers say that for one app to have everything they’d need, it would have to incorporate advanced photo- and video-editing tools and a highly precise eraser. And it would have to be flexible enough to adapt to new formats in real time.

Julia Enthoven, Silicon Valley veteran of Google and Apple, co-founded Kapwing, a photo- and video-editing app, nine months ago in order to patch what she saw as a huge hole in the market. “You can see it in the Google search trends. The search volume for ‘meme maker’ has more than doubled since September 2017,” Enthoven says.

Keeping track of modern meme trends, and nailing details like the precise font options or default spacing between photos and text, can be a challenge for those not completely immersed in the meme world. George Resch, a memer with more than 1.6 million followers on Instagram under the handle @tank.sinatra, and his co-founder, @adam.the.creator, who has nearly half a million followers on Instagram, are betting that their deep knowledge of meme culture will give them a competitive advantage. They released their meme-making app, Momus Meme Studio, in January and have seen usage grow exponentially.

“I think people trust what we use because we are known as the backbone of the meme community,” says Resch. He and his team spent hours on the phone with the developers building the app, trying to get it to look exactly right. “If you look at the pixels of space at edge of a picture, we talked about that for weeks ... There’s apps out there that don’t pay any attention to that and it shows,” Resch says.

Chris Rosiak, the co-founder and CEO of Red Blue Media, which owns memes.com and @memes on Instagram and Facebook, also launched its own meme-making app, Memes Generator + Meme Creator, three months ago and saw an immediate explosion of use. The app is now on top of search results for meme makers in the App Store and has received thousands of positive ratings. In order to stay relevant, Memes Generator + Meme Creator employs a team of people who search for emerging meme trends on Instagram, Twitter, and “meme incubation zones” like Reddit and 4Chan. “We’re looking at the things that are going viral and trending and incorporating it into the app,” Rosiak says.

Conner Jay, head of audience at Elsewhere, a video-focused meme-creation app that launched in December, says that being one with the meme community is key to success. The app’s user base is 80 percent 13 to 24-year-olds, and Jay says they can tell when things aren’t authentic. “Our team is very squarely in our 20s. We have a video editor who has been a professional shitposter for years,” he says. The company also does a huge amount of outreach on college campuses and pays students to create memes for its owned channels.

But awareness remains the biggest hurdle for newer meme apps. Several big memers say they mostly only hear about new products through group chats with peers. “We have a bunch of group chats and we’re all good about sharing things with each other,” says Jacob, who memes under the handle @WipeYaDocsOff.

Still, Jeff, who memes under the handle @CtrlCtrl, says that those just starting out shouldn’t be too intimidated by the intricate formats they might come across on the Explore page.

“If you’re funny and you have ideas that are good, just keep messing around with whatever works for you,” he says. “There’s so many apps out there, so many ways to do it. I was never very tech-savvy and it took me a while to get to the point that I’m at now. It took me a long time to find the right recipe.”

The paeans to Tom Wolfe, who died on Monday at the age of 88, inevitably extol his colorfully inventive use of language across his decades of fiction and nonfiction writing. As the New York Times obituary observes, “He had a pitiless eye and a penchant for spotting trends and then giving them names, some of which—like ‘Radical Chic’ and ‘the Me Decade’—became American idioms.”

Wolfe’s contributions to the English language go far beyond the most obvious catchphrases that he popularized. The Oxford English Dictionary includes about 150 quotations from Wolfe’s writings, and in many cases, he is the earliest known source for words and phrases that have worked their way into the lexicon. Here is a survey of some of his key linguistic innovations.

As an early proponent of what came to be known as New Journalism, Wolfe had a flashy sense for language from the very beginning: Consider the title of his 1963 essay that put him on the map, a piece for Esquire on custom cars: “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy Kolored (Thphhhhhh!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (Rahghhh!) Around the Bend (Brummmmmmmmmmmmmmmm)…”

A year later, an essay of Wolfe’s for Harper’s Bazaar titled “The New Art Gallery Society” provided the first of his many OED-anointed neologisms: aw-shucks as a verb meaning “to behave with (affected) bashfulness or self-deprecation.” Describing a party for the reopening of the Museum of Modern Art, Wolfe wrote, “Up on the terrace, Stewart Udall, the Secretary of the Interior of the United States, is sort of aw-shucksing around.”

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, his 1968 account of Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, introduced a number of terms straight out of the drug-fueled counterculture, like Owsley, for “an extremely potent, high-quality type of LSD” (named after Owsley Stanley, the Grateful Dead soundman who manufactured millions of doses of acid). The book also brought us edge city, defined by the OED as “a notional place outside the bounds of conventional society” (“It’s time to take the Prankster circus further on toward Edge City”), and the adjective balls-out, defined as “unrestrained, uninhibited” (“The trip, in fact the whole deal, was a risk-all balls-out plunge into the unknown”).

Wolfe was clearly in a neologistic frame of mind in 1970, when he wrote two of his most famous essays. From “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” published in New York, we of course get radical chic (“the fashionable affectation of radical left-wing views”), though he seems to have appropriated the phrase from Seymour Krim, who had used it earlier in the year in his collection of essays Shake It for the World. And the title of “Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers” contributed two more coinages: mau-mauing (“using menacing or intimidating tactics against”), and flak catcher (“one who deals with and deflects adverse or hostile comment, questions, etc., in order to protect a person or institution from unfavorable publicity”).

A 1976 New York cover story is responsible for one of Wolfe’s most enduring phrases: “The ‘Me’ Decade and the Third Great Awakening.” Along with me decade as his term for the 1970s (“regarded as a period characterized by an obsessive preoccupation with personal fulfillment and self-gratification”), the OED credits Wolfe with a lesser-known expression: hardballer in the sense of “a person who is ruthless and uncompromising, esp. in politics or business” (as in: “Charles Colson, the former hardballer of the Nixon Administration, announces for Jesus”).

Wolfe once again picked a title that was destined for lexical immortality when he wrote his 1979 book on the Project Mercury astronauts, The Right Stuff. Though the right stuff is actually documented by the OED back to 1748 in the sense of “something that is just what is required” (especially alcohol or money), Wolfe’s book provided a new semantic twist: “the necessary qualities for a given job or task,” that mysterious essence imbuing the test pilots drafted for the Mercury program.

The Right Stuff also helped popularize some expressions that were previously known only in aviation and aeronautics circles. One is push the envelope, meaning “to approach or go beyond the current limits of performance,” which the OED notes had appeared in the magazine Aviation Week & Space Technology a year before Wolfe brought it to a mainstream audience. Another is screw the pooch, meaning “to make a (disastrous) mistake,” which Wolfe famously used in recounting Virgil “Gus” Grissom’s botched splashdown after becoming the second American in space. The movie version reinforced the notion that Grissom had screwed the pooch, though the malfunction was likely not the astronaut’s fault. (For a deep dive into how screw the pooch evolved from the earlier expression fuck the dog, see my 2014 piece for Slate.)

Wolfe kept up his penchant for concocting new words in the go-go ’80s, such as his coinage of plutography, a play on pornography. “This may be the decade of plutography,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1985, explaining that “plutography is the graphic description of the acts of the rich.” At the time, Wolfe was busy working on his own plutographic opus: his first novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities, published in 1987.

The most notable expression to come out of The Bonfire of the Vanities is Master of the Universe, though that phrase actually dates back to the work of John Dryden in 1690, with the meaning “a person or being that controls everything.” In the early 1980s, “Masters of the Universe” took on a new life for Mattel’s superhero franchise of He-Man, She-Ra, and the rest, spun off into action figures, comic books, and animated TV series. Wolfe’s protagonist Sherman McCoy applies that omnipotent term to the financial world: “On Wall Street he and a few others—how many?—three hundred, four hundred, five hundred?—had become precisely that … Masters of the Universe. There was … no limit whatsoever!”

Bonfire also illustrated Wolfe’s keen ear for the vernacular, with different characters voicing the now-famous New York City refrain, fuhgedaboudit. To take the example cited by the OED, Goldberg, a police detective, says, “In the Bronx or Bed-Stuy, fuhgedaboudit. Bed-Stuy’s the worst.” Former Brooklyn borough president Marty Markowitz must not have taken the knock against Bedford-Stuyvesant to heart, since during his tenure he put “Fuhgeddaboutit” on a highway sign leaving Brooklyn, showing how the interjection had become firmly entrenched as a tongue-in-cheek marker of local identity.

Wolfe’s later novels (A Man in Full, I Am Charlotte Simmons, and Back to Blood) were not quite as fertile for introducing new words, though he continued to keep tabs on developments in the language. The germ for I Am Charlotte Simmons came from a 2000 essay, “Hooking Up,” that investigated the “hook-up” culture of American college students. But Wolfe was hardly in the forefront on this, as Connie Eble reports in her book Slang and Sociability that undergraduates at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill were using hook up to mean “to find a partner for romance or sex” since the mid-’80s. While Wolfe at the end of his career may have moved from being a linguistic leader to merely a follower, his decades of creativity with the written word have undoubtedly left an enduring impact.